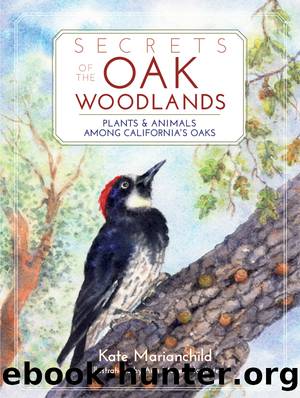

Secrets of the Oak Woodlands by Kate Marianchild

Author:Kate Marianchild

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781597143721

Publisher: Heyday

To survive, this Oregon oak seedling needs mycorrhizal fungi, neighboring trees, and rodents. Here, the seedlingâs root tip has been colonized by a fungal spore from old rodent droppings and is now sending out hyphae (magnified). The vole will dig up and eat the truffle produced by the mature oakâs hyphae and disperse its spores.

As vascular plants evolved and differentiated over millions of years, more and more plant-fungus partnershipsâmycorrhizasâformed. They were probably widespread 65.5 million years ago, when an asteroid larger than Mt. Everest crashed into what we now know as the Yucatan Peninsula. The impact blasted out a crater 112 miles in diameter and sent a glowing cloud of vaporized rock radiating northwest. Heat and shock waves instantly killed all the animals and plants within hundreds of miles. Debris and smoke from massive forest fires drifted around the earth, shrouding it in darkness. Ninety percent of all leaf-bearing plants on earth and 70 percent of all animals, including most of the dinosaurs, died. Fungi, which donât depend on light for energy, thrived in the shadowy new world and, in the words of mycologist Paul Stamets, âinherited the earth.â There are at least six times as many species of fungi than plants in the world today.

At the time of this Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-PG) extinctionââthe second largest in the history of the earthââmany plants that had formed mycorrhizal relationships were able to survive, while most others died. Plant-fungus relationships became so important, in fact, that they have persisted into the present and probably constitute the most widespread and important symbiosis on earth. About 95 percent of all land plants, including grasses, trees, and crop plants, are dependent on fungi.

During much of each year, mycorrhizal fungi exist only under the surface of the ground as hyphae, whose one-cell-thick filaments branch and rejoin frequently to create spongy networks known as mycelium. Hyphae are so abundant in forests that if you dug up all the threads underneath one of your feet and lined them up end to end, they might stretch as far as three hundred miles!*

The hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi glean water and mineralsââphosphorus, nitrogen, zinc, and copperââfrom soil and transport them to plants, effectively expanding the plantsâ root systems and boosting nutrient uptake by up to one hundred times what it would be without them. They tap water from soil pores too tiny for root hairs, and they can keep plants alive during droughts by penetrating and extracting water from rock, even granite. They store extra plant sugars in their mycelium, making them available to plants as needed.

Mycorrhizal fungi also improve the immunity of plants and carry chemical messages between them. In a 2013 study, plants attacked by aphids âtoldâ neighboring plants about it via the mycorrhizal internet. Their neighbors, who hadnât yet been attacked, responded by producing chemicals that simultaneously repelled aphids and attracted aphid-eating wasps!

In addition to assisting individual plants, mycorrhizal fungi âmanageâ forests for maximum health and diversity. They influence whether and where seedlings get established and, like modern-day Robin

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15293)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14461)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12352)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12071)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12000)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5740)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5408)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5382)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5283)

Paper Towns by Green John(5157)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4979)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4474)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4472)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4423)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4370)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4318)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4297)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4167)